.png)

Most companies adopting Iceberg aren't starting from scratch. They have years of data in Hive tables or raw Parquet files, and migrating that data without disrupting existing pipelines is the real challenge.

Iceberg supports Parquet, ORC, and Avro files natively, and provides procedures to convert existing tables without rewriting the underlying data. But in-place migration has limitations, and for some tables rewriting or even starting fresh makes more sense. The right approach depends on how much data you're dealing with, whether you need historical data, and how your tables are partitioned.

Let's go through the options.

Why Migrate to Apache Iceberg?

If your Hive tables are working fine, you might wonder why migration is worth the effort. The short answer is that Iceberg solves several long-standing problems with Hive that become painful at scale.

ACID transactions are probably the most significant improvement. Iceberg provides full ACID guarantees by default - every write creates a new snapshot, and readers always see a consistent view of the table regardless of concurrent writes. This matters when you have multiple pipelines writing to the same table.

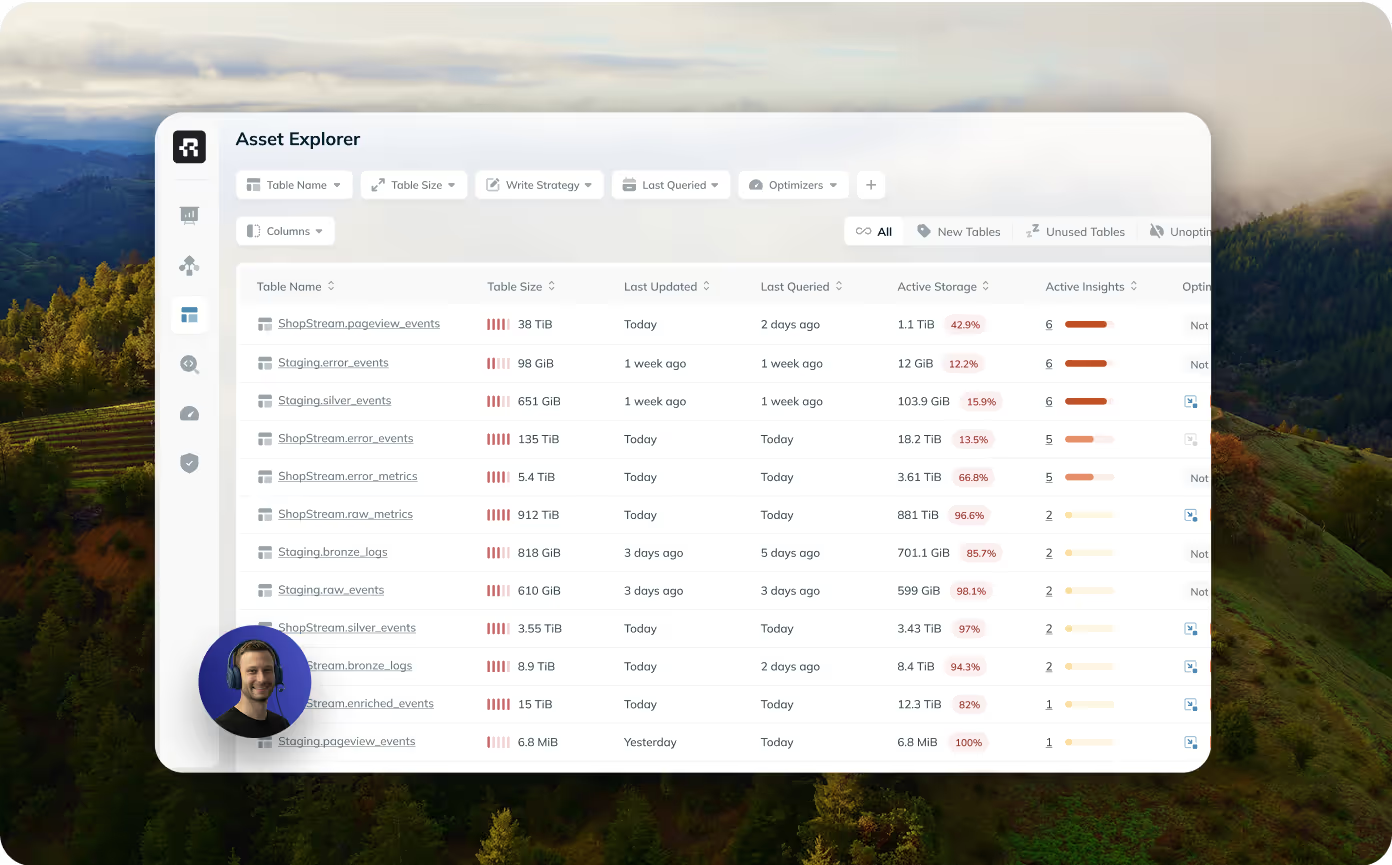

Time travel lets you query historical versions of your data by referencing previous snapshots. You can run queries against the table as it existed at a specific timestamp or snapshot ID, which is useful for debugging, auditing, and recovering from bad writes. Hive doesn't have this capability natively. The challenge is that you can't keep snapshots forever - we recently announced Iceberg Backups in Ryft to help teams maintain reliable recovery points without unbounded storage growth.

Hidden partitioning eliminates one of the most common sources of user error in Hive. With Hive, users need to know how a table is partitioned and include the correct partition predicates in their queries. Get it wrong and you scan the entire table. Iceberg tracks partition information in its metadata and automatically applies partition pruning based on any filter that matches the partition transform, even if users don't know the table is partitioned.

Partition evolution lets you change how a table is partitioned without rewriting existing data. In Hive, changing the partition scheme means creating a new table and migrating all your data. Iceberg handles this transparently - old data stays in the old partition layout, new data uses the new layout, and the query engine handles both correctly.

Schema evolution allows you to add, rename, or drop columns without rewriting existing data. Iceberg tracks schema changes in its metadata and handles the mapping automatically - queries against old data files work correctly even after the schema has changed. Hive supports some schema changes, but the behavior is inconsistent and often requires careful coordination between the metastore and the underlying files

Broader engine support is increasingly important as data platforms become more diverse. Iceberg tables work across Spark, Trino, Flink, Athena, Snowflake, and most other modern query engines without format conversion or data duplication. You're not locked into a single engine ecosystem.

Before You Start: Key Considerations

Before moving on to procedures and tooling, there are two questions that will shape your entire migration strategy.

Do You Need Historical Data?

This sounds obvious, but it's worth thinking through carefully. If your use case only queries recent data - say, the last 30 days of events - you might not need to migrate years of historical Hive tables at all. You could start writing new data to Iceberg today and let the old Hive tables age out naturally, or keep them around as a read-only archive.

On the other hand, if analysts regularly query historical data for trend analysis or compliance requires you to maintain queryable records going back years, you'll need to migrate that history. The answer here determines whether you're migrating terabytes or petabytes.

How Much Data Are We Talking About?

The volume of data you're migrating affects which approach makes sense. Iceberg provides in-place migration procedures that convert tables without copying data files, but these come with limitations. If you're migrating a 10 TB table, in-place migration saves significant time and storage costs. If you're migrating a 100 GB table, it might be simpler to just create a fresh Iceberg table and run an INSERT...SELECT from the Hive source

The threshold depends on your environment, but as a general rule: if the data is small enough that you can afford to rewrite it, rewriting is often cleaner than in-place migration. You get a fresh start with proper Iceberg column identifiers, you can restructure partitions using hidden partitioning, and you don't inherit any quirks from the original Hive table layout.

Migration Strategies

There are three main approaches to migrating from Hive to Iceberg, and they're not mutually exclusive - you might use different strategies for different tables.

Strategy 1: Start Fresh

The simplest approach is to stop writing to your Hive tables and start writing to new Iceberg tables instead. This works well when historical data isn't critical or when you're willing to maintain the old Hive tables as a read-only archive.

The process is simple:

- Create a new Iceberg table with the schema you want

- Update your ingestion pipelines to write to the Iceberg table

- Query the Hive table for historical data and the Iceberg table for new data (or create a view that unions them)

- Eventually, deprecate the Hive table when the data is no longer needed

This approach has zero migration risk because you're not touching the existing data. The downside is that you temporarily have data split across two systems, which can complicate queries that span the transition period.

Strategy 2: Rewrite the Data

If you want to fully migrate a table including historical data, rewriting gives you the cleanest result. You create a new Iceberg table and populate it by reading from the Hive source:

CREATE TABLE iceberg_catalog.db.events (

event_id BIGINT,

event_time TIMESTAMP,

user_id STRING,

event_type STRING,

payload STRING

)

USING iceberg

PARTITIONED BY (days(event_time));

INSERT INTO iceberg_catalog.db.events

SELECT * FROM hive_catalog.db.events;

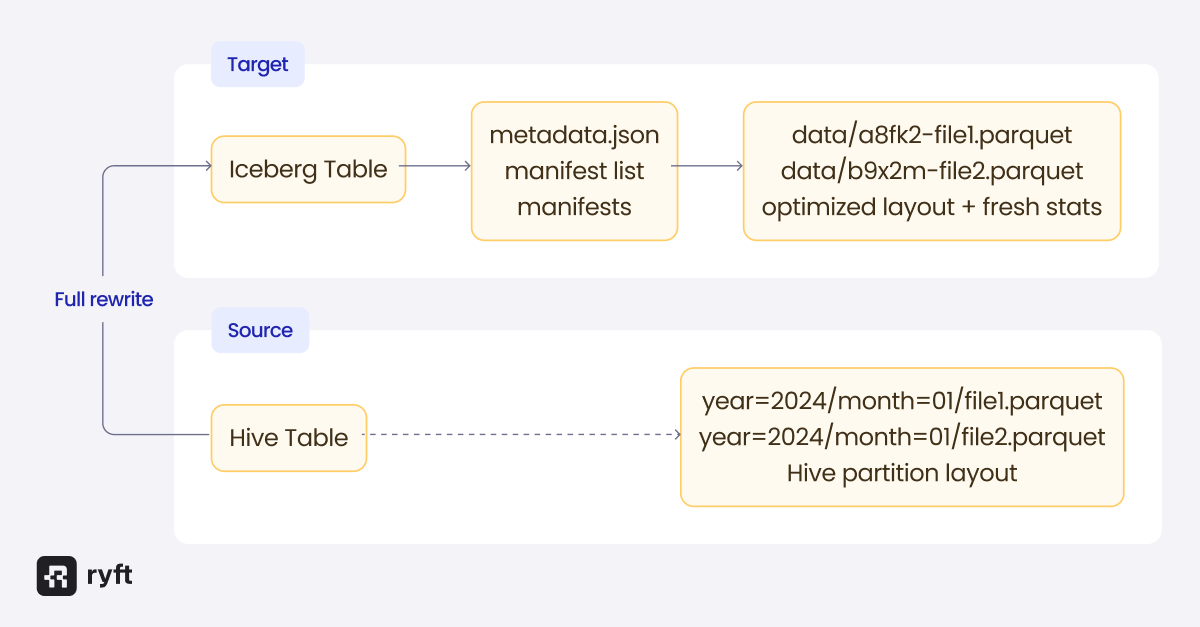

This approach has several advantages. You can restructure partitions using Iceberg's hidden partitioning transforms (like days(event_time) above) rather than inheriting Hive's explicit partition columns. Rewriting also generates fresh statistics - min/max values, null counts, and other metadata that Iceberg stores in manifests and data files. These statistics enable query engines to skip irrelevant files and improve query performance significantly. We covered how Iceberg statistics work in a previous post. You can also choose the target location, which matters if you're migrating to a different storage bucket or want to use Iceberg's object store layout for better S3 performance.

The cost is that you're reading and writing all your data, which takes time and temporarily doubles your storage usage. For large tables, this can be expensive.

Strategy 3: In-Place Migration

Iceberg provides procedures that convert Hive tables without copying data files. This is the fastest option for large tables and doesn't require additional storage, but it comes with limitations.

The key procedures are:

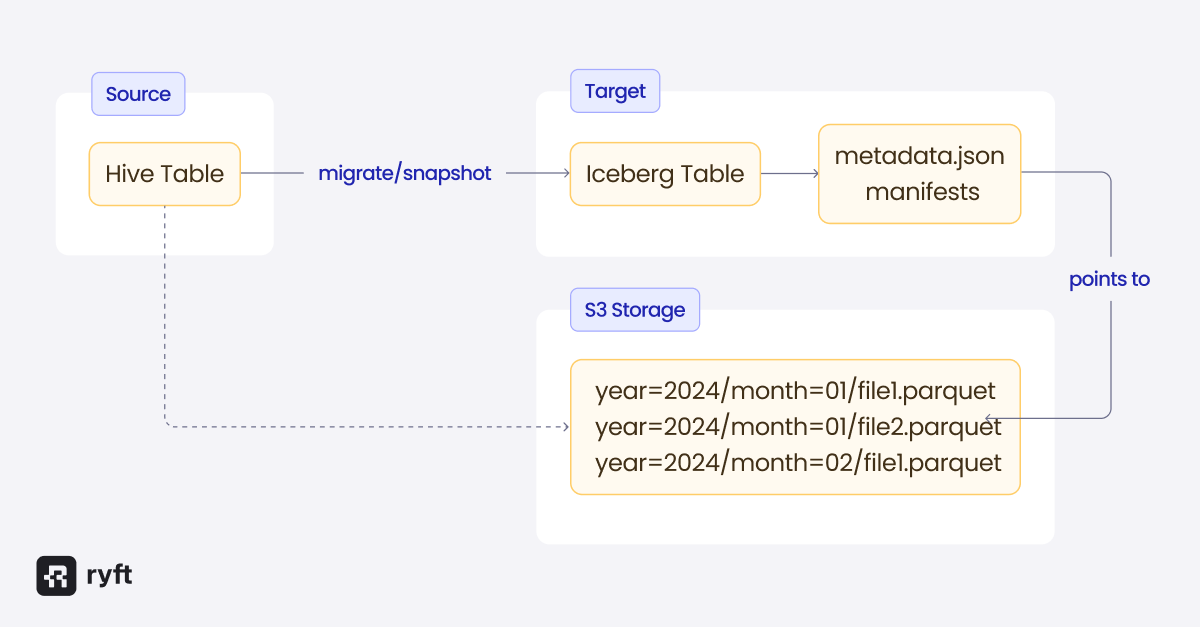

snapshot - Creates a new Iceberg table that references the existing Hive table's data files without modifying the original. This is useful for testing the migration before committing to it.

migrate - Replaces the Hive table with an Iceberg table in place. The original table's schema, partitioning, and location are preserved. By default, a backup of the original table definition is retained.

add_files - Adds data files from a Hive table (or a directory of files) to an existing Iceberg table. Unlike migrate, this doesn't create a new table - it adds files to a table you've already created.

Let's look at each of these in detail.

The Migration Procedures

These procedures are available in Spark and Trino. The syntax differs slightly between engines, but the concepts are the same.

Snapshot: Test Before You Commit

The snapshot procedure creates a new Iceberg table that points to the existing Hive table's data files without modifying the original. This lets you test read compatibility, verify that queries return correct results, and experiment with Iceberg features before committing to the migration.

In Spark:

CALL catalog_name.system.snapshot('db.hive_events', 'db.iceberg_events');This creates db.iceberg_events as an Iceberg table that references the same data files as db.hive_events. You can query the new table, verify the results, and even write new data to it - new writes go to the Iceberg table's location, not the original Hive location.

Since the snapshot table uses the original Hive table’s data files, you should not perform any action that edits those files (such as expire_snapshots). The table should be used temporarily for testing, then either proceed with a full migration or drop them.

Migrate: Replace the Table In-Place

The migrate procedure converts a Hive table to Iceberg in-place. After migration, the table becomes an Iceberg table and can be accessed through the Iceberg catalog.

In Spark:

CALL catalog_name.system.migrate('db.events');This replaces db.events with an Iceberg table. The schema, partitioning, and data location are preserved. The original table definition is saved with the `_BACKUP_` suffix by default (e.g. db.events_BACKUP_).

You can customize the behavior:

CALL catalog_name.system.migrate(

table => 'db.events',

properties => map('write.format.default', 'parquet'),

drop_backup => false,

backup_table_name => 'db.events_old'

);A few things to keep in mind:

- Migration fails if any partition uses an unsupported file format (CSV, JSON, etc.). Only Parquet, ORC, and Avro are supported.

- The existing data files are not rewritten - Iceberg creates metadata that references them in place.

That last point is both the advantage and the limitation of in-place migration. You save time and storage, but you don't get the benefits that come with rewriting the data:

No fresh statistics. The migrate procedure doesn't scan the data files - it only reads file-level metadata like paths and row counts. Iceberg manifest-level statistics (min/max values, null counts) won't be populated for migrated files, which limits file skipping optimizations. The original statistics in Parquet/ORC file footers still exist, but not all query engines use them.

No hidden partitioning. If you migrate a Hive table with explicit year=/month=/day= partitions, that layout remains. This “simple” layout doesn’t have all the benefits of Iceberg partition transforms. You can add a new partition spec like day(timestamp), but it only applies to new writes - the migrated data keeps its original structure.

No layout optimization. Hive tables typically use path-based layouts that create hotspots on object stores like S3. Migrated tables retain their original paths rather than using Iceberg's optimized object store layout.

Name-to-ID column mapping. Iceberg identifies columns by ID rather than name, which is what makes schema evolution safe. But existing files don't have Iceberg's column IDs embedded, so Iceberg creates a name-to-ID mapping instead. This works, but it's less robust for complex schema changes than files written natively by Iceberg.

Add Files: Incremental Migration

The add_files procedure adds data files from a Hive table or directory to an existing Iceberg table. Unlike migrate, it doesn't create a new table - you must create the Iceberg table first.

This is useful for incremental migration scenarios where you want to migrate partitions gradually, or when you need to add data from external sources that aren't registered as Hive tables.

In Spark:

-- First, create the target Iceberg table

CREATE TABLE iceberg_catalog.db.events (...) USING iceberg;

-- Add files from a Hive table

CALL spark_catalog.system.add_files(

table => 'iceberg_catalog.db.events',

source_table => 'hive_catalog.db.events'

);

-- Or add files from a specific partition

CALL spark_catalog.system.add_files(

table => 'iceberg_catalog.db.events',

source_table => 'hive_catalog.db.events',

partition_filter => map('date', '2024-01-15'));

-- Or add files directly from a path

CALL spark_catalog.system.add_files(

table => 'iceberg_catalog.db.events',

source_table => '`parquet`.`s3://bucket/path/to/data`'

);There are important warnings with add_files:

- Schema is not validated. If the source files have a different schema than the target Iceberg table, you'll get errors at query time, not during the add operation.

- Files added this way become owned by Iceberg. Subsequent expire_snapshots calls can delete them.

- Partition values come from paths, not data. The procedure infers partition values from Hive-style directory paths (like date=2024-01-15/hour=12/), not from the actual data in the files. If your files aren't laid out this way, Iceberg can't determine the partition values and will assign nulls - even if the data itself contains the correct values. This can result in a malformed table where partition filters don't work correctly and queries scan more data than they should. For non-Hive partitioned data, you'll need to either reorganize the files first or use the rewrite approach instead.

Coordination During Migration

One of the most common problems with migration is coordinating producers and consumers. When you migrate a table to Iceberg, new writes must go through Iceberg's commit path. You can't just keep adding files to the old Hive table location and expect Iceberg to pick them up - Iceberg tracks files in its metadata, and files added outside of Iceberg commits won't be visible.

This means your ingestion pipelines and your analytics queries need to transition together, or you risk having producers writing data that consumers can't see.

The safest approach is:

- Stop writes to the Hive table

- Run the migration procedure

- Update ingestion pipelines to write to Iceberg

- Resume writes

For tables with continuous ingestion, this might require a brief maintenance window.

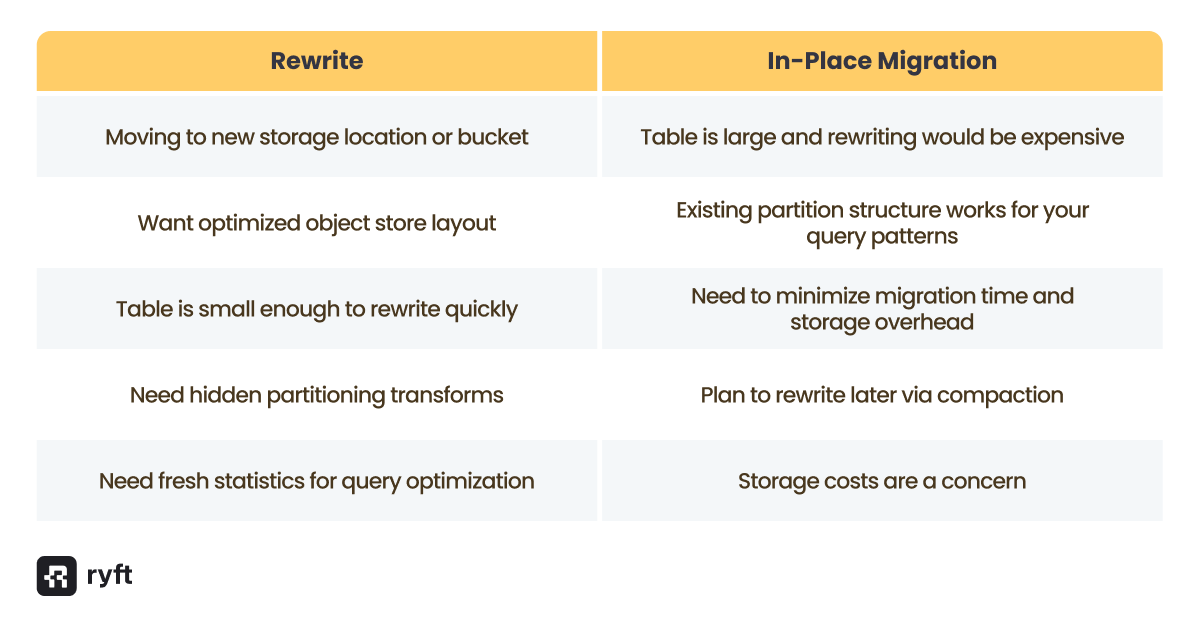

Rewriting vs. In-Place: When to Choose Each

The migration procedures leave existing data files in place, which is fast but doesn't give you the benefits of a full rewrite. Here's when to choose each approach:

Catalog Considerations

Before starting your migration, make sure your catalog supports both Hive and Iceberg table formats - you need to read the Hive table and write the Iceberg table through the same or connected catalogs. Most popular catalogs support both, including Hive Metastore and AWS Glue. If yours doesn't, you'll need to configure separate catalogs and ensure both can access the underlying storage.

We covered catalog selection in depth in a previous post - the key point here is that your catalog choice affects what migration paths are available to you.

Final Thoughts

Migrating from Hive to Iceberg doesn't have to be a big-bang project. The right approach can be chosen per table, based on data volumes, query patterns, and the necessity of retaining historical data.

For small tables, the most straightforward method is often to rewrite the data directly into new Iceberg tables. For large tables, the migration procedures will let you convert in-place without duplicating massive datasets. And if historical data isn't critical, starting fresh with Iceberg for new data avoids the migration complexity entirely.

Lastly, remember that migrating the data and metadata is the first half of the job. The next challenge lies in your producers and consumers - pipelines need to be rewritten to follow the Iceberg spec, queries need to point to the new tables, and the switchover needs to be orchestrated carefully to avoid downtime or data inconsistencies.

Browse other blogs

Unlocking Faster Iceberg Queries: The Writer Optimizations You’re Missing

Apache Iceberg query performance is often limited long before a query engine gets involved. In a joint post with Firebolt, we break down why writer configuration, file layout, and continuous table maintenance matter most.

.avif)

.avif)