One of the most common patterns in modern data lakes is replicating operational databases into analytical storage.

Your production MySQL database holds customer orders, your PostgreSQL instance tracks user activity, and your MongoDB stores product catalogs - but running analytical queries against these systems puts load on your operational infrastructure and doesn't scale for complex analytics workloads.

Change Data Capture solves this problem. Instead of querying operational databases directly or running expensive nightly snapshots, CDC captures every insert, update, and delete as they happen in the source database and streams those changes to your data lake in near real-time.

The Core Concepts Behind CDC

CDC works by reading from the database's internal transaction log rather than querying the database itself. Every relational database maintains a durability log - it might be called a binlog in MySQL, a WAL in PostgreSQL, or a redo log in Oracle - but the concept is the same. This log records every change that happens in the database, and CDC tools read from this log to capture changes without impacting the operational workload.

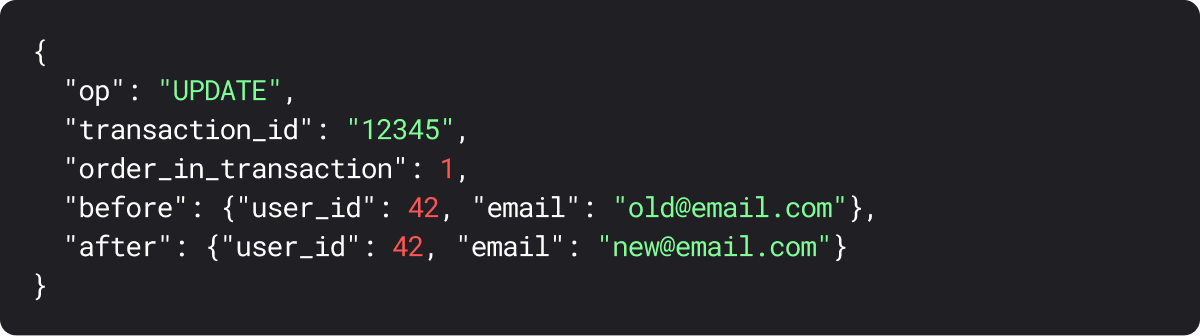

A CDC event contains specific information about what changed:

- Operation type: Whether this is an INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE

- Transaction ID: A unique identifier for the transaction, which helps maintain ordering

- Row data: Either the full row or just the changed fields, depending on the CDC tool configuration

Here's what this looks like - when a user updates their email address, the CDC event might look like:

Getting CDC Data from Source Systems

Several tools can read from database transaction logs and emit CDC events. The most common ones are:

Debezium is an open-source CDC platform that started as a Kafka Connect source connector and has evolved to support multiple outputs. It reads from MySQL binlogs, PostgreSQL WAL, MongoDB oplogs, and several other database types, then streams those changes to Kafka or other systems. The benefit of Debezium is that it's free and highly configurable, but you need to run and maintain the infrastructure.

AWS Database Migration Service is a managed service that captures changes from various databases and can write them either to a stream like Kafka or Kinesis, or directly to S3 as files. DMS is popular in AWS environments because it requires minimal infrastructure management, though it's less flexible than running your own CDC tooling.

Flink CDC is a newer option that uses Apache Flink to read directly from database logs and can write changes straight into Iceberg tables. This approach combines the CDC capture and ingestion steps into a single pipeline.

The typical architecture involves one of these tools reading from your source database's transaction log and writing the change events to either a streaming system like Kafka or directly to object storage like S3. From there, you need to get those changes into Iceberg, and this is where you have strategic choices to make.

CDC Ingestion Strategies for Iceberg

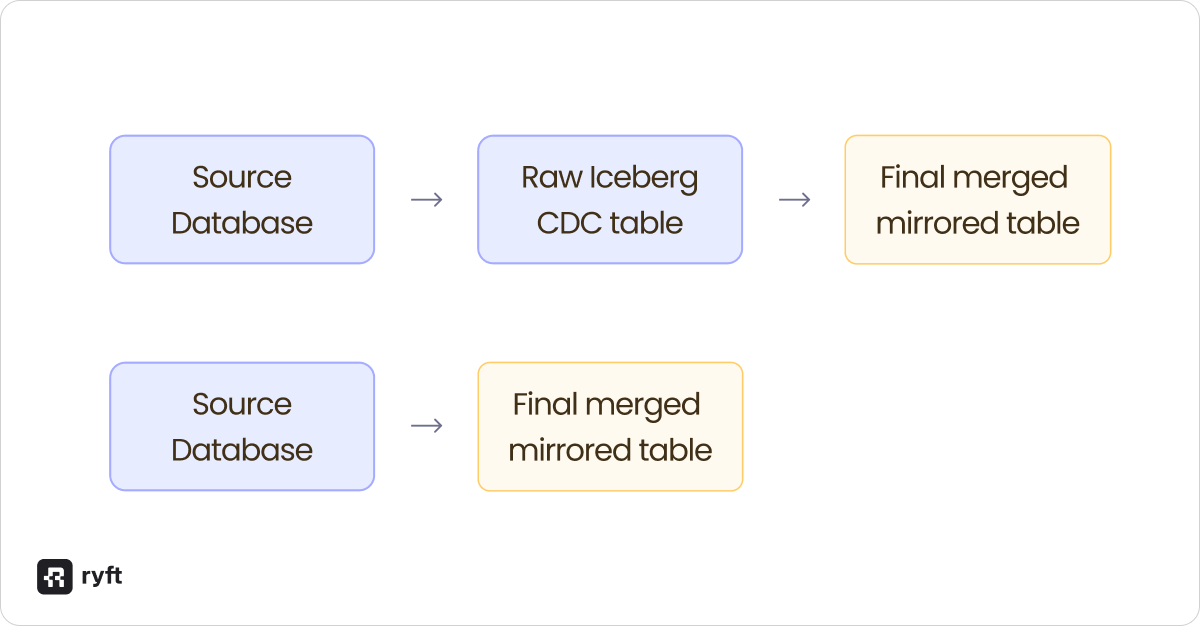

There are two main approaches to getting CDC data into Iceberg, and the choice between them involves real considerations around flexibility versus simplicity.

Approach 1: Direct Materialization

Tools like Flink CDC can read from your source database and write directly to a final Iceberg table that mirrors your source table structure. The CDC tool handles the merge logic internally - when it sees an UPDATE event, it automatically finds and updates the corresponding row in your Iceberg table. When it sees a DELETE, it removes that row.

This approach is simple to set up and requires minimal custom code. You configure the tool to connect to your source database and point it at your target Iceberg table, and it handles the rest. The downside is that you're limited by what the tool supports - if you need custom transformation logic or want to handle schema evolution in a specific way, you're constrained by the tool's capabilities.

Approach 2: Raw Change Log + ETL

The alternative is to first write the raw CDC events to a "bronze" Iceberg table that simply appends every change event as it arrives. This bronze table is append-only, so it's fast to write to and captures the complete history of every change. Then you run a separate ETL process that reads from this bronze table and materializes the final "mirror" table that reflects the current state of your source database.

With this approach, you maintain two tables:

- Bronze CDC table: Contains every INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE event with operation metadata

- Mirror table: The final materialized table that shows the current state of your source data

Your ETL process reads incrementally from the bronze table and uses MERGE INTO statements to apply those changes to the mirror table. This could be a Spark job, a Flink pipeline, or even SQL queries run on a schedule.

The benefit here is complete flexibility - you control exactly how merges are handled, you can add custom transformation logic, and you can replay history if something goes wrong by reprocessing from the bronze table. For example, many teams choose to ignore specific events, such as deletes, to retain more data in the lake than in the operational database. The cost is that you need to build and maintain this ETL pipeline yourself.

Challenges with CDC at Scale

Running CDC into Iceberg works well at small scale, but several operational challenges appear when you're processing high volumes of changes.

CDC Creates Heavy Update Workloads

Unlike append-only data ingestion, CDC involves constant updates and deletes. If you're replicating a user's table with 10 million rows and your application updates user properties regularly, you might be updating thousands of rows per second. Each update in Iceberg requires either rewriting data files (Copy-on-Write) or creating delete markers (Merge-on-Read), and this work compounds quickly.

Partition Layout Impacts CDC Performance

How your source data is structured obviously affects CDC performance in Iceberg. Consider two scenarios:

Time-based tables like event logs or transaction histories are easier to handle because most CDC activity hits recent partitions. When you're appending new events and occasionally updating recent records, you're only touching a small subset of partitions. Compaction can focus on the active partitions while older partitions remain stable.

Entity tables like users or products are more challenging because updates can touch any partition. If you partition a user's table by user_id and run an operation that updates all users with a new property, you've just modified every single partition in the table. This means your compaction and merge operations need to read and rewrite files across the entire table, not just recent partitions.

The partition strategy for your mirror table needs to match your query patterns, but be aware that CDC workloads will stress that strategy. A poorly chosen partition scheme can make CDC merges extremely slow.

Copy-on-Write vs Merge-on-Read

This choice becomes important in CDC workloads because you're constantly updating records.

With Copy-on-Write, every update rewrites the entire data file containing that record. If you have 1MB files with 1000 rows each and you update 10 rows spread across 10 different files, you're rewriting 10MB of data even though only 10 rows changed. For high-volume CDC, this creates massive write amplification and increases latency.

Merge-on-Read writes small delete files instead of rewriting data files, which keeps write latency low. The downside is query performance - readers need to process both data files and delete files, then merge them at query time. This typically requires a more robust compaction to periodically merge delete files back into data files, or query performance will degrade as delete files accumulate.

For CDC workloads, Merge-on-Read is usually the better choice because it keeps the ingestion pipeline fast, but you need to commit to running regular compaction jobs to manage the delete files.

Tool Simplicity vs Ingestion Flexibility

The direct materialization approach (Flink CDC writing straight to your mirror table) is simpler because the tool handles everything. You don't write merge logic, you don't manage two tables, and you don't orchestrate an ETL pipeline. But this simplicity comes at the cost of control - you're dependent on what the tool supports and how it handles edge cases.

The raw change log approach gives you full control over the merge logic and lets you customize schema evolution, handle late-arriving data however you want, and replay history when needed. But you're responsible for writing and maintaining that merge pipeline, which means more code to test and more infrastructure to manage.

This isn't an either/or decision - you can also build the raw change log approach yourself with Spark or other engines, giving you the same flexibility with different tradeoffs around cost and complexity. The key is understanding what level of control you need versus how much operational overhead you're willing to take on.

Wrap Up

CDC into Iceberg works at scale in production data lakes, but getting it right means understanding the considerations involved.

The core decision is between direct materialization and the raw change log approach. Direct tools like Flink CDC are simpler to operate but give you less control over the merge logic. The raw change log pattern requires maintaining two tables and a merge pipeline, but it preserves complete history and gives you full flexibility over how changes are applied.

For CDC workloads at scale, Merge-on-Read is typically the right write mode because it keeps ingestion latency low, but this means you need robust compaction to manage delete files. Your partition strategy matters more than in append-only workloads because CDC updates can touch partitions across the entire table depending on your source data structure.

If your use case allows it, keeping the raw CDC change log provides valuable flexibility. When something goes wrong - bad data gets ingested, events arrive out of order, or you need to adjust your merge logic - having the complete history lets you roll back and replay from a known good state. The storage cost of keeping this raw data is usually worth the operational flexibility it provides.

Browse other blogs

Unlocking Faster Iceberg Queries: The Writer Optimizations You’re Missing

Apache Iceberg query performance is often limited long before a query engine gets involved. In a joint post with Firebolt, we break down why writer configuration, file layout, and continuous table maintenance matter most.

.avif)

.png)

.avif)